ML Groom Deformer

This is one of the projects I presented at the Houdini HIVE Horizon event hosted by SideFX in Toronto. You can watch the full presentation here. I’ll go into more specific setup details in this text summary. You can find an almost identical version of the text (better formatting) on the SideFX tutorial page and download the project files from the content library.

# General Idea

In essence, the goal is to predict how fur deforms on a character or creature using a machine learning model, instead of relying on expensive simulations and procedural setups.

The setup is based on the ML Deformer example that was included in the content library with the release of Houdini 20.5.

# The Problem

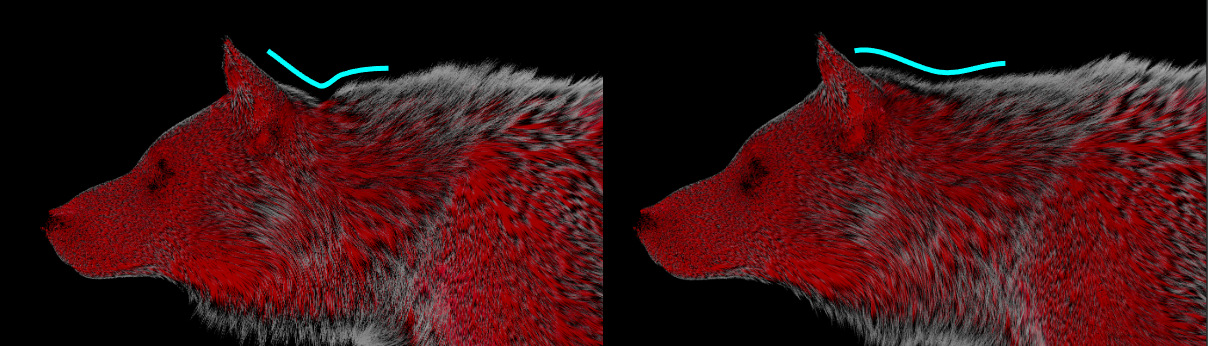

There are a few common issues when deforming hair naively or linearly. Particularly around the joint areas, there are numerous intersection problems, where hair above the joint pierces through the fur layer below (see the second position in the graphic below). Ideally, we want to see a nice layering of guides and better volume preservation. Achieving this can be computationally expensive and often requires a simulation along with one or more post-processing steps to get right.

Left to right: Rig, Default Guide Deform, Ideal Deformation (Quasi-Static Simulation), Rest Guides, Displacement in Rest Space

# The Solution

Our goal is to predict the deformation that needs to be applied to the guides based on the rig position using an ML model. The model learns to map from the rotation data of each rig joint to the approximated displacement of the guides for each pose.

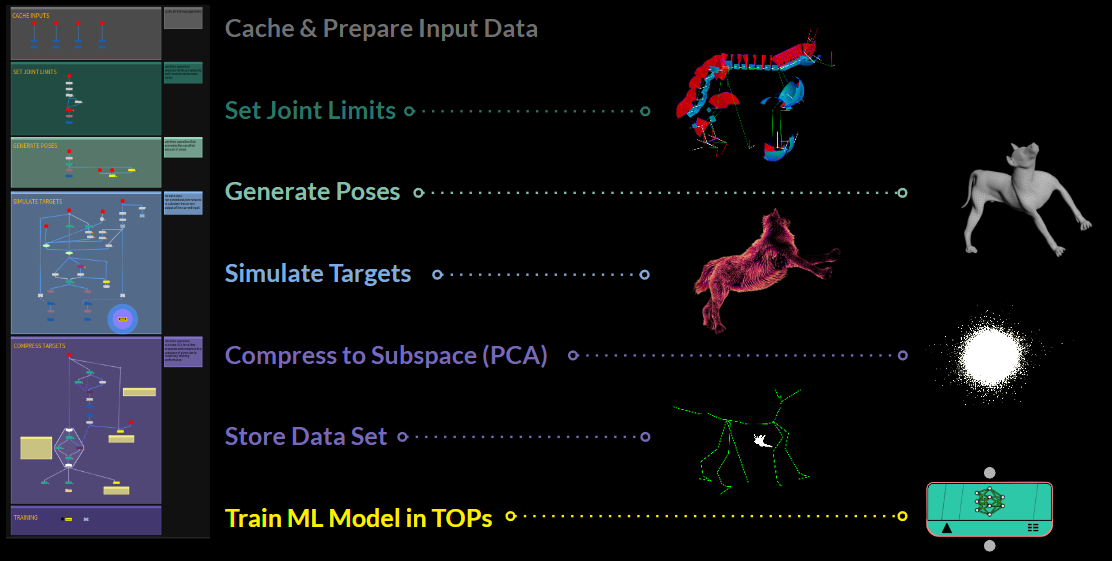

To do this, we need a substantial number of examples for the model to learn from. The general pipeline looks something like this:

- Define joint limits on our rig (fixed values or automatically in a procedural fashion)

- Generate a bunch of random poses based on these joint limits (think 3000 or more / we need good coverage)

- Simulate a ground truth/good guide deformation for each pose

- Collect all deformations and compress the data into a PCA subspace (conceptually the hard part)

- Store the full preprocessed dataset to disk

- Train a ML model in TOPs(which is actually the easy part)

# Data Generation

To generate all the training data we need 2 things to start out with:

- a rigged model of a character/creature (in this case the wolf)

- a set of guides

# Joint Limits

This could be a set degree value on each joint (e.g., 30) or, preferably, if we have a few motion clips for the rig, we can procedurally configure the joint limits based on the range of motion present in our clips. To do this, use the configure joint limits SOP.

# Pose Randomization

In Houdini 20.5, a new node was introduced to streamline this process. The ml pose generate SOP takes existing joint limits and generates random poses in a Gaussian distribution. This means there will be more normal poses than extreme ones, which is desirable for training a model that performs well in common positions.

The output is a bunch of posed packed rigs stacked on top of each other.

# Simulation Loop

In this stage we run over each of our generated poses using TOPs and generate/simulate a good guide deformation result accordingly.

This step could be almost anything. There is just a few limitations:

The result has to be deterministic / procedural / quasi-static!

That means we can’t have any inertia (think jiggle, overshoot, simulation goodness) and we should always get the same result when we rerun the same inputs. Also the inputs should influence the outputs in a smooth way. Additionally, the relationship between inputs and outputs should be smooth; similar inputs should yield closely related results. So, let’s avoid any noise that might lead to wildly different outcomes for nearly identical inputs.

In this case I’m using a combination of a quasi-static tet simulation and a de-intersection pass, in which the guides are advected through a velocity field built from the hair and skin.

# Create Pose Blend Animation

In this step we blend over from the rest position to the target rig position to create an animation we use to drive our simulation.

# Quasi-Static Tet Simulation (Vellum)

To simulate the main part of the fur a tet cage is built from the guides to simulate the volume of the fur and how it deforms. This is very useful for avoiding guide-to-guide collisions and ensures correct layering of fur by design.

To generate the tet cage I use some simple VDB operations:

guides > VDB from particles > reshape dilate close erode >tet conform

The tet simulation runs in vellum on quasi-static mode. The red interior points get pinned to the animation to move the soft body with it.

After applying the deformation with a point deform we get rid of all the jagged edges and most of the intersections. The volume of the whole groom gets preserved too.

# De-Intersection through Velocity Advection

To clean up any left over guide intersections we advect the guides through a velocity field that is built from the normals of the skin mesh and the tangents of the guides themselves. Due to the nature of velocity fields the guides basically de-intersect themselves and the flow gets clean up a little on the way there. I first saw this technique in Animalogic’s talk about their automated CFX pipeline.

# Ground Truth Examples

After all of this we end up with one correctly deformed set of guides per pose:

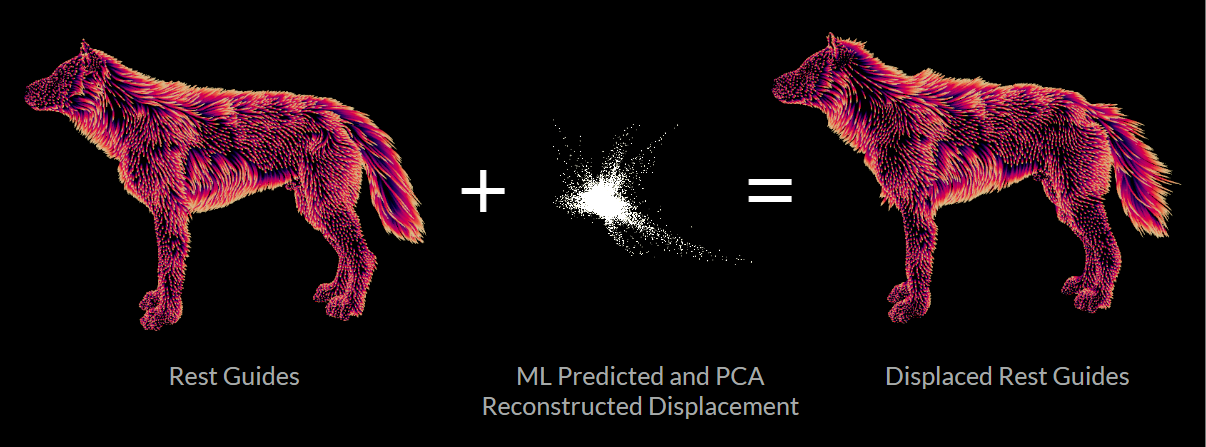

# Calculate Rest Displacement

We need to then move each of these poses back into rest space using the classical guide deform node. In rest space we compute the difference of each point on the deformed guides to the rest guides using the shapediff SOP. This gives us a clean point cloud we will store together with the rig position as one training example.

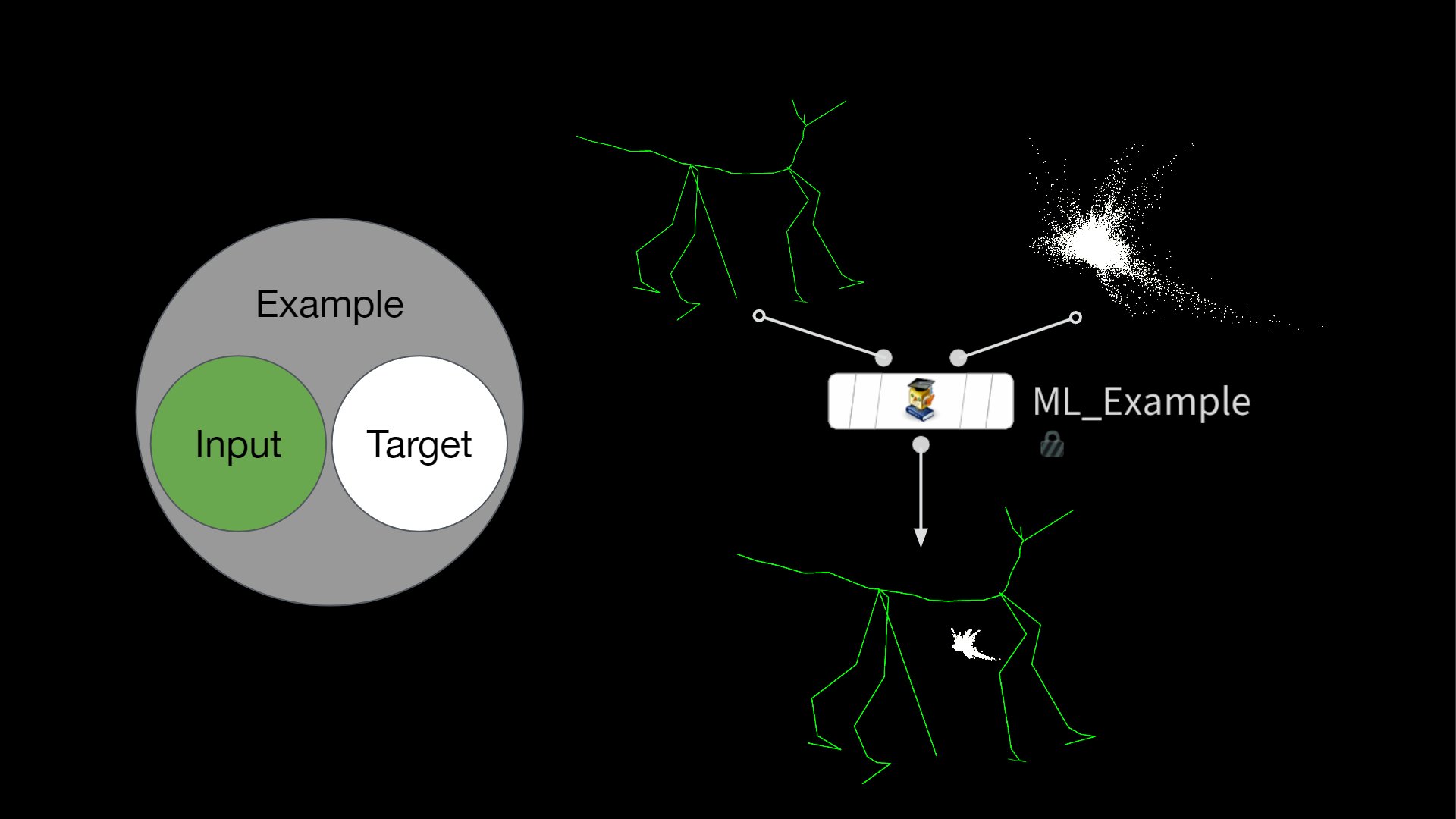

# Storing the Examples

Once all of the poses are simulated and the displacement is generated we can start assembling what is called an ML Example in Houdini. Usually this is called a data sample. It consists of an input and a target and is one of the many examples we show the network during training to make it (hopefully) learn the task at hand.

To do this we can use the ml example SOP, which packs each of the inputs before packing the merged pairs again. This ensures data pairs stay together and don’t get out of sync somehow downstream.

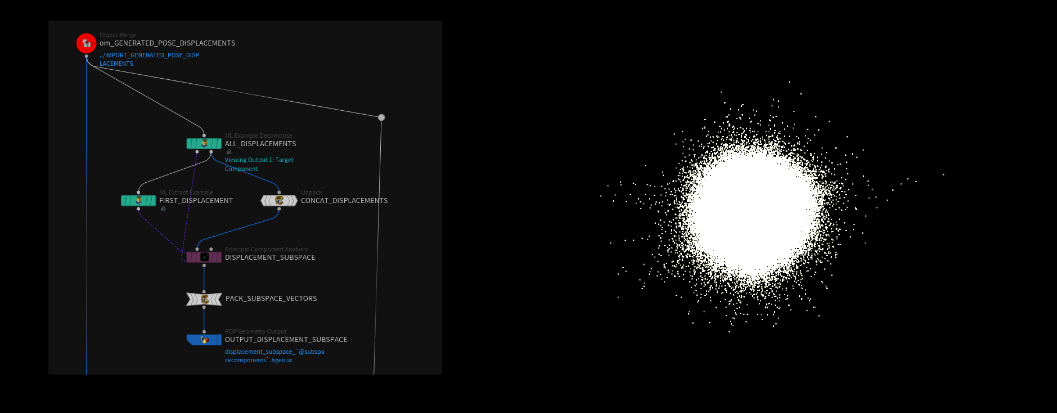

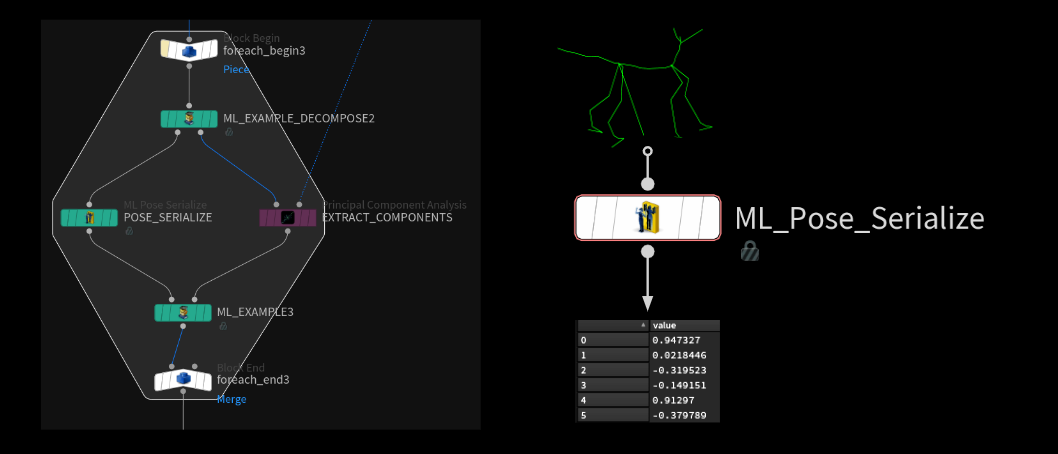

# PCA Subspace Compression and Serialization

After generating all of our pose displacements we bring in those points and merge them all together and calculate our PCA subspace.

If we want to read more on Principal Component Analysis, I tried to explain it in a non mathy way here.

# Creating the Subspace

We let PCA do the math magic and compress our 4000 examples down to fewer components. In this case we can think of it as inventing new, but fewer blendshapes of the original displacements that (if combined correctly) can reconstruct all of our inputs accurately.

This PCA-generated point cloud is all of the new components (invented blend shapes) stacked on top of each other. They aren’t separated in any way in Houdini (not packed, no ids or anything). We determine which points belong to each component by understanding the size of the sample. For example, if our dataset contains 100,000 points, we can identify the components by examining the list of points. The first component consists of points from 0 to 99,999 (ptnum 100k-1), while the second component includes points from 100,000 to 199,999 (ptnum 200k-1), and so forth.

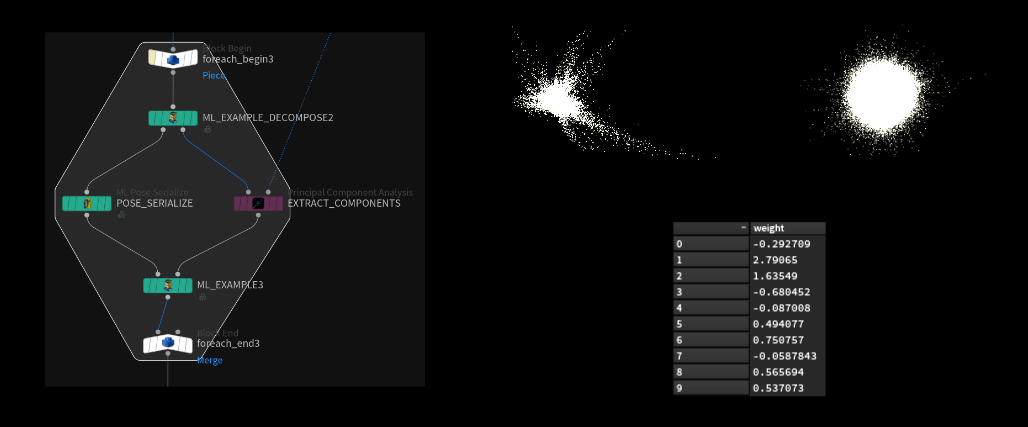

# Calculating the Weights per Example

In the next step we will calculate how much of each component (blend shape) we need to combine to reconstruct each original displacement.

We loop over each example and let PCA “project” (PCA math term for calculating the weights) our displacement points onto the subspace. This returns a list of weights that correspond to the amount of components in the subspace.

Those weights can later be applied to the subspace point cloud to reconstruct the original displacement point cloud (close enough at least).

The reconstruction will never be 100%, but we can reach 95%+ levels while using only a few hundred components. Hair guides are especially tricky to compress, because of the high point count (100.000+ points) and the missing relationship between individual hair stands.

For things like skin geometry (think muscle or cloth deformer) we can usually get away with much fewer components (64-128 possibly) and still reach high reconstruction accuracy.

# Why Do All This?

Instead of having to learn 100.000 point positions (300k float values), we only need the model to predict the weights needed for reconstruction (64, 128, 512, 1024 floats or whatever we choose). The size of our network stays small and training and inference is much faster that way. Performance would also suffer immensely, trying to map a few joint rotation values to a giant list of point position values.

# Serialization

On the other side of that for loop we serialize the joint transforms using the new ml pose serialize SOP. All this node does is take the 3x3 matrices stored on each joint and map the values to a -1 to 1 range and store each float of that matrix on a single point in series. We end up with a long list of float values which represent our joint rotation data. This is necessary because neural networks don’t like matrices as a single input. It’s easier to only work with single float values. The mapping to the -1 to 1 range makes sure it plays nicely with activation functions inside the network.

# Data Set Export

After postprocessing all the examples we can write out the full data set to disk. The ml example output SOP stores all the samples together in a single data_set.raw file, which will be read by the training process later on.

# Training

The training is completely done inside of TOPs. There isn’t too much to it after having done all that preparation work, which does the heavy lifting and is the process that takes the most amount of time (to setup and to run all the simulations as well).

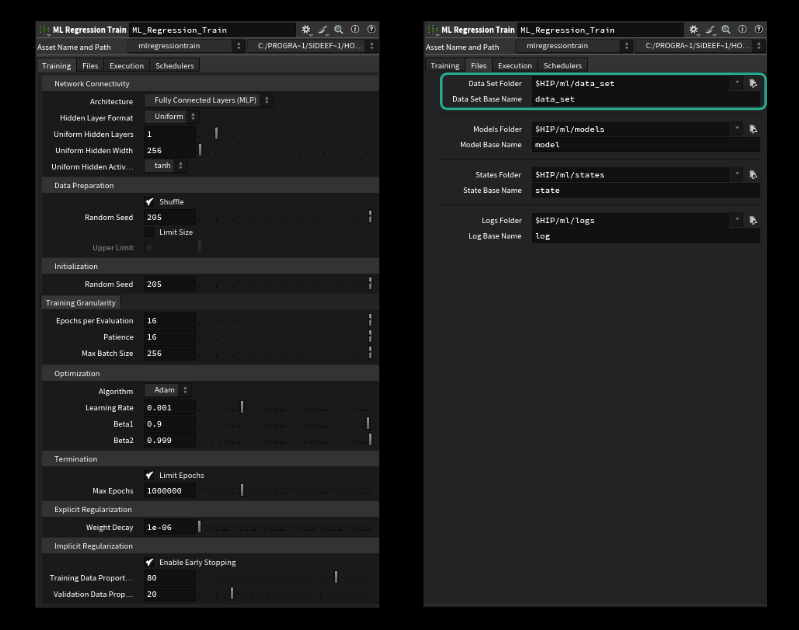

# ML Regression Train

The core of the whole system is the ml regression train TOP, which is a wrapper around PyTorch under the hood. We can set all the common training parameters on there and it comes with some nice quality of life features, such as splitting our dataset automatically in training and validation data based on a ratio we can specify.

We can also control all the parameters of the network (called hyperparameters for some obscure ml reason).

The most important ones are:

- Uniform Hidden Layers (how big is our network in width)

- Uniform Hidden Width (how many “neurons” each layer has)

- Batch Size (how many examples to look at before adjusting the weights > average)

- Learning Rate (how big the steps are the model takes towards the goal / think jumping down mountain or walking carefully)

To start training something we only need to make sure to specify the correct directory and name of our dataset on the files tab. By default this should be correct though. Be careful: Only specify the filename without the extension. It won’t run if we add the .raw. (last tested in H20.5.370)

# Wedging

Having all those parameters available on the node in TOPs opens the door to do some wedging! This is common practice and is usually called hyperparameter tuning. We could run multiple experiments to find the right combination of parameters that give we the best performing model. The parameters I mentioned above are a good place to start wedging. For the groom deformation example here I only wedged the amount of layers and the size of each layer.

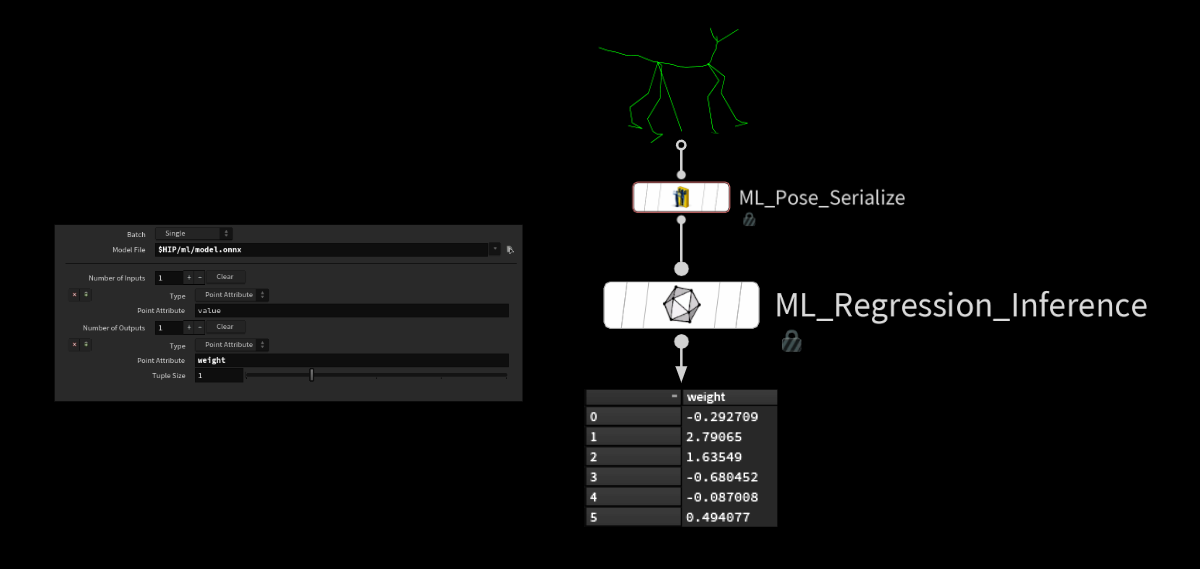

# Inference

Or doing everything in reverse..

Inference is the process of applying the model to new inputs. To do this we need to make sure the inputs come in in the exact same shape as they did when training.

So we serialize the new rig pose before applying our model using the ml regression inference SOP. This SOP is just a simpler version of the onnx inference SOP. It takes the model and some info on what values to read/write from where (points or volumes).

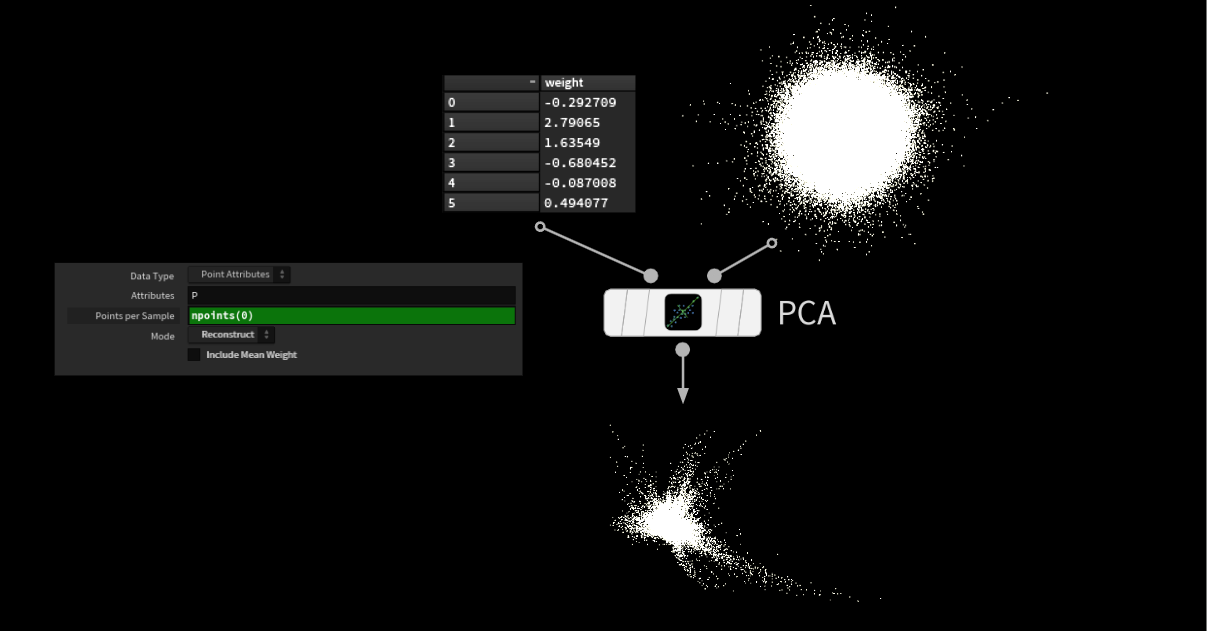

The model then spits out a list of weights, which we can use to reconstruct our displacement based on the subspace components we saved earlier.

Feed those two into a PCA node and let it do it’s thing. This gives us the displacement we need to deform the guides. The rest should be pretty straight forward. Apply the predicted displacement to our guides by adding each vector to the corresponding point on the curves.

That gives us a jagged looking ruffled up wolf. But if we deform it into the correct position the displacement is based on we get a smooth looking result.

Here’s a frame by frame preview where I blend back and forth between the original linear guide deform and the ml prediction

Also we can measure and visualize the error of our prediction. The number is the RMSE (Root Mean Squared Error) of all the point differences. The color visualizes the local error compared to the ground truth on the right.

# Results

Here’s a few more screenshots and renders of how this could affect a full groom:

# Credits

Thanks to the amazing team at SideFX for all the help with this project!

Support on All Fronts: Fianna Wong ML Tools Developer: Michiel Hagedoorn Wolf Model & Groom: Lorena E’Vers CFX Help: Kai Stavginski & Liesbeth Levick

sources / further reading: